News Story

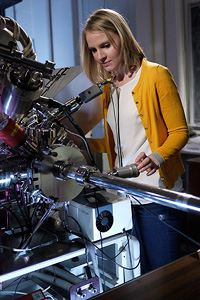

Marquardt Studies Patinas at Smithsonian Institution

Department of Materials Science and Engineering (MSE) graduate student Amy Marquardt, advised by Professor Ray Phaneuf, spent the summer at the Smithsonian Institution's Museum Conservation Institute (MCI), where she worked with Smithsonian research scientist Dr. Edward Vicenzi and MSE adjunct professor Dr. Richard Livingston (NIST) on a project that could help museums better analyze, clean and preserve their bronze artifacts.

The research focused on patinas, the greenish films that form on untreated metal surfaces (typically copper, bronze, and brass) after years of exposure to the elements—for example, a patina is what gives the Statue of Liberty its minty color. Patinas help protect metal against further corrosion, and may increase an object's value. An artificial patina can also be applied to an object to accelerate the process, produced a desired look, or restore a patina after cleaning. Artificial patinas, however, are not as stable and long lasting as the real thing.

"In the field of conservation, cleaning and repatination of bronze statues is an active area of research," Marquardt explains, "but the chemistry and mineralogy of the artificial patinas used by artists and conservators have not been systematically and quantitatively investigated. The purpose of our research was to understand, at the molecular and microstructural level, the relationship between the application of artificial patination to bronze and the resulting appearance and stability of the patina. Understanding both the process and its result is important for the conservation and restoration of bronze objects."

Marquardt and her colleagues used scanning electron microscopy, electron probe microanalysis, and Raman spectroscopy to determine patina color, mineralogy, stability and interactions with protective coatings for different artificial bronze patina recipes. Marquardt also worked with corrosion samples taken from Auguste Rodin's Eve, a sculpture belonging to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Her goal was to characterize the corrosion in order to aid conservators in the restoration and cleaning of the piece.

"The best thing about the internship was that the nature of the project required an interdisciplinary collaboration between materials science, conservation, art history, and mineralogy," she says of the experience. "It has been very interesting and I have enjoyed meeting and working with the scientists and conservators at the Smithsonian and NIST."

Learn More:

Visit the Museum Conservation Institute's web site »

Published August 25, 2010